The Great Green Wall: Africa’s epic quest to beat desertification

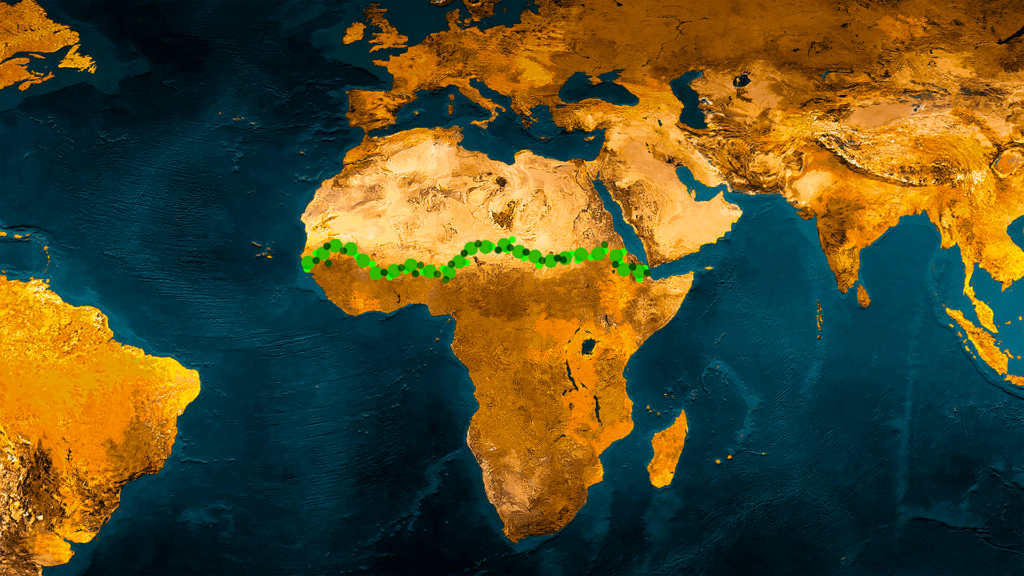

In a bid to combat the relentless advance of desertification in the Sahel region, the African Union started an ambitious initiative: The Great Green Wall. With the support of local communities and governments, the aim is to combat desertification and degradation in the Sahel region, the southern border with the Sahara Desert. Proposed in 2007, the main goal is to create a mosaic of green landscapes 8,000 kilometers long and 15 kilometers wide – a literal wall – to revive soil fertility, biodiversity, and forests along the way.

The initiative involves 11 countries in the Sahel region and is supported by over 20 countries worldwide. The goal, set by 2030, is to restore 100 million hectares of degraded landscapes, with trees capable of sequestering up to 250 million tons of carbon from the atmosphere, and to create 10 million jobs.

Today, the initiative spans the continent, with participating countries including Burkina Faso, Chad, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Sudan.

What on Earth (literally) led to its existence?

The project emerged in response to increasing desertification (or just ultimate land degradation, you choose), fueled by climate change, extreme temperatures, and unsustainable farming practices, causing loss of biodiversity, fertility, and productivity.

Desertification is a threat to society and individuals living there: when agricultural productivity is threatened, food security and the quality of life in these countries are also at risk. Consequently, communities already heavily affected by climate change and rapidly rising temperatures become more susceptible to hunger, drought, armed conflicts, and poverty. This problem worsens across sub-Saharan Africa, posing risks to the survival of millions of people.

Contrary to common perception, the Great Green Wall is not just about planting trees for soil recovery but also about promoting agroforestry and sustainable management that keeps the soil fertile and prevents drought, often without the need to plant new trees in the region. Thus, it isn’t just about a singular solution but rather an orchestration of sustainable practices and interdisciplinary efforts.

Life is not a bed of roses…

To be realistic, the current progress of the wall varies among participating countries. While some of them are sprinting ahead, fueled by funding and support, like Senegal, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Niger, others are mired in a financial quagmire, held back by conflicts both social and military, plus the slow pace of the donations, like Sudan, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Chad – in the middle of these conflicts, there’s little money to be spared with conservation projects.

… but it’s not all doom and gloom, either!

Yet, as of 2020, the initiative had already breathed life back into 20 million hectares of land and created 350,000 jobs, proving that even in the toughest battles, there’s room for growth.

The progress of the Great Green Wall highlights the interconnectedness of soil and nature: when the soil degrades, it affects forests and agricultural activities; this, in turn, threatens food and water security, as well as causes armed conflicts, rural migration, and forced migration.

So, what’s the moral of the story? When land thrives, people and biodiversity do too.

In a world where everything is interconnected, where actions in one corner of the globe ripple across the planet, the Great Green Wall is a symbol of our shared responsibility in safeguarding our environment and ensuring a better future for all.